Isidor Buchmann, Cadex Electronics, Inc

The battery, today’s technological necessity, is the result of 400 years of scientific effort.

One of the most remarkable and novel discoveries in the last 400 years is electricity. One may ask, “Has electricity been around that long?” The answer is yes and perhaps much longer, but the practical use of electricity has only been at our disposal since the mid to late 1800s. One of the early electrical attractions that gained public attention was an electrically illuminated bridge over the Seine River during the 1900 World’s Fair in Paris.

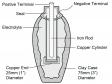

The use of electricity may go back much farther. While constructing a new railway in 1936 near Baghdad, workers uncovered what appeared to be a prehistoric battery. The discovery was known as the Baghdad or Parthian battery (see Figure 1) and was believed to be 2000 years old, dating back to the Parthian period [The Parthian empire existed in what is now Iran from 247 BC-224 AD. — Ed.]. The battery consisted of a clay jar filled with vinegar. An iron rod surrounded by a copper cylinder penetrated into the liquid and produced 1.1 to 2 V of electricity.

Not all scientists accept the Parthian battery as being a source of energy because the application is unknown. [There are alternative explanations for the Parthian battery but it does work as a battery. — Ed.] It is possible that the battery was used for electroplating a layer of gold or other precious metals onto a surface. The Egyptians are said to have electroplated antimony onto copper over 4300 years ago.

Modern Battery Experiments

The earliest method of generating electricity was by inducing a static charge in some substance. In 1660, Otto von Guericke (1602-1686) constructed the first electrical machine consisting of a large sulphur globe that, when rubbed and turned, attracted feathers and small pieces of paper. Guericke was able to prove that the sparks generated were electrical in nature. The first practical use of static electricity was the “electric pistol,” which was invented by Alessandro Volta (1745-1827). An electrical wire was placed in a jar filled with methane gas. When an electrical spark was sent through the wire, the jar would explode.

Volta (see Figure 2) then thought of using this invention to provide long distance communications, albeit only one Boolean bit. An iron wire supported by wooden poles was to be strung from Como to Milan, Italy. At the receiving end, the wire would terminate in a jar filled with methane gas. To signal a coded event, an electrical spark would be sent by the wire to detonate the electric pistol. This communications link was never built.

In 1791, while working at the University of Bologna, Luigi Galvani (1737-1798) discovered that the muscle of a frog contracted when touched by dissimilar metallic objects. This phenomenon became known as “animal electricity” — a misnomer, as was later proved. Prompted by these experiments, Volta initiated a series of experiments using dissimilar metals. He tried combining zinc, lead, tin or iron as positive plates and copper, silver, gold or graphite as the negative plates.

Early Batteries

Volta discovered in 1800 that certain fluids would generate a continuous flow of electrical power when combined with a pair of dissimilar metals. This discovery led to the invention of the first voltaic cell, more commonly known as a battery. Volta discovered further that the voltage would increase when voltaic cells were stacked on top of each other. Figure 3 illustrates such a serial connection.

In the same year, Volta released his discovery of a continuous source of electricity to the Royal Society. No longer were experiments limited to a brief display of sparks that lasted a fraction of a second. A seemingly endless stream of electric current was now available.

France was one of the first nations to officially recognize Volta’s discoveries. France was approaching the height of scientific advancements and new ideas were welcomed with open arms. By invitation, Volta addressed the Institute of France in a series of lectures at which Napoleon Bonaparte was present as a member (see Figure 4). Napoleon helped with the experiments, drawing sparks from the battery, melting a steel wire, discharging an electric pistol and decomposing water into its elements.

After Galvani’s successful experiments and the discovery of the voltaic cell, interest in galvanic electricity became widespread. Sir Humphry Davy (1778–1829), inventor of the miner’s safety lamp, made new discoveries when he installed the largest and most powerful electric battery into the vaults of the Royal Institution. He connected the battery to charcoal electrodes and produced the first electric light. Witnesses reported that his voltaic arc lamp produced “the most brilliant ascending arch of light ever seen.”

Davy began to test the chemical effects of electricity in 1800 and soon found that by passing electrical current through some substances, decomposition occurred, a process later called electrolysis. The generated voltage was directly related to the reactivity of the electrolyte with the metal. Davy understood that the actions of electrolysis and the voltaic cell were the same.

In 1802, Dr William Cruickshank designed the first electric battery capable of being mass produced. Cruickshank arranged square sheets of copper with equal sheet sizes of zinc. These sheets were placed into a long rectangular wooden box and soldered together. Grooves in the box held the metal plates in position. The sealed box was then filled with an electrolyte of brine, or watered down acid, resembling the flooded battery that is still with us today (see Figure 5).

Rechargeable Battery

In 1836 John F. Daniell, an English chemist, developed an improved battery that produced a steadier current than Volta’s device. Until then, all batteries were primary, meaning that they could not be recharged. In 1859, the French physician Gaston Planté invented the first rechargeable battery. It was based on lead and acid, a system that is still used today.

In 1899, Waldmar Jungner from Sweden invented the nickel-cadmium battery (NiCd), which used nickel for the positive electrode and cadmium for the negative. Two years later, Thomas Edison produced an alternative design by replacing cadmium with iron. High material costs compared to dry cells or lead acid systems limited the practical applications of the nickel-cadmium and nickel-iron batteries. It was not before Shlecht and Ackermann achieved major improvements by inventing the sintered pole plate in 1932 that NiCd gained new attention [sintering is the process of fusing nickel powder at a temperature well below its melting point using high pressures]. This resulted in higher load currents and improved longevity. The breakthrough came in 1947 when Neumann succeeded in completely sealing the nickel-cadmium cell.

In the 1980s and 1990s, the attention was on nickel-based chemistries. Concerned about environmental contamination if NiCd was carelessly disposed, some European countries began restricting this chemistry and asked the industry to switch to nickel metal hydride (NiMH). Many say that the NiMH is an interim step to lithium-ion (Li-ion) and this may well be true. Much of the research focuses on improving lithium-ion batteries. Besides powering cellular phones, laptops, digital cameras, tools and medical devices, Li-ion is also a candidate for vehicles. Li-ion has a number of benefits including a higher energy density, is easier to charge and does not have maintenance issues unlike nickel-based batteries. Nor does Li-ion suffer from sulfation that is common with lead-based systems.

Electricity through Magnetism

Electricity through magnetism, an alternative method of generating electricity besides static charge and battery, came relatively late. In 1820, André-Marie Ampère (1775-1836) noticed that wires carrying an electric current were at times attracted and at other times repelled from one another. In 1831, Michael Faraday (1791-1867) demonstrated how a copper disc provided a constant flow of electricity while revolving in a strong magnetic field. Faraday, assisting Davy and his research team, succeeded in generating an endless electrical force as long as the movement between a coil and magnet continued. This led to the invention of the electric generator and then the electric motor. Shortly thereafter, transformers were developed that could convert alternating current (ac) to any desired voltage. In 1833, Faraday established the foundation of electrochemistry by publishing his laws of electrolysis.

Once the relationship with magnetism was discovered in the mid 1800s, large generators began producing a steady flow of electricity. Motors followed that enabled mechanical movement and the Edison light bulb appeared to conquer darkness. The three-phase ac technology developed by Nikola Tesla (1857-1943) enabled transmission lines to carry electric power over great distances. Electricity was thus made available to humanity to improve overall quality of life.

The invention of the electronic vacuum tube in the early 1900s was the significant next step toward high technology, enabling the development of frequency oscillators, signal amplifications and digital switching. This led to radio broadcasting in the 1920s and the first digital computer called ENIAC in 1946. The discovery of the transistor in 1947 paved the way to the integrated circuit 10 years later. The microprocessor ushered in the Information Age and revolutionized the way we live today.

Humanity depends on electricity, and with increased mobility, people are moving more and more toward portable power storage — first for wheeled applications, then portability and finally wearable use. As awkward and unreliable as the early batteries may have been, future generations may look at today’s technologies as nothing more than clumsy experiments.

History of Battery Development.

1600 William Gilbert (UK) Establishment of electrochemistry study

1791 Luigi Galvani (Italy) Discovery of “animal electricity”

1800 Alessandro Volta (Italy) Invention of the voltaic cell

(zinc and copper disks)

1802 William Cruickshank (UK) First electric battery capable

of mass production

1820 André Marie Ampère (France) Electricity through magnetism

1833 Michael Faraday (UK) Announcement of Faraday’s laws

1836 John F. Daniell (UK) Invention of the Daniell cell

1839 William Robert Grove (UK) Invention of fuel cell (H2/O2)

1859 Gaston Planté (France) Invention of the lead-acid battery

1868 Geroge Leclanché (France) Invention of the Leclanché

cell (carbon-zinc)

1899 Weldmar Jungner (Sweden) Invention of the

nickel-cadmium battery

1901 Thomas A, Edison (USA) Invention of the

nickel-iron battery

1932 Shlecht and Ackermann Invention of the

sintered pole plate

1947 Neumann (France) Successfully sealing the

nickel-cadmium battery

1949 Lew Uir, Eveready Battery (USA) Invention alkaline-manganese

battery

1970s Group effort Development of valve regulated

lead-acid battery

1990 Group effort Commercialization of nickel-metal

hydride battery

1991 Sony (Japan) Commercialization of

lithium-ion battery

1996 Moli Energy (Canada) Introduction of Li-ion

with manganese cathode

2005 Valence, A123 System (USA) Introduction of Li-ion with

phosphate cathode

Illustrations from Cadex Electronics Inc.

Isidor Buchmann is the founder and CEO of Cadex Electronics Inc, a Canadian company specializing in the design and manufacture of advanced battery testing instruments. He has studied the behavior of rechargeable batteries in practical, everyday applications for two decades. As an award-winning author of many articles and books on the subject, Mr Buchmann has delivered battery-related technical papers around the world. You can find more battery information at Cadex’s battery university. Isidor can be contacted at 22000 Fraserwood Way, Richmond, BC V6W 1J6, Canada.